In this guest post, Cathal McDaid, Chief Technology Officer at AdaptiveMobile Security takes a detailed look at a recent SMS phishing campaign undertaken against an Irish bank, and documents some new twists to the attack not seen before in the hope of preventing their effectiveness elsewhere.

SMS phishing, sometimes referred to as ‘smishing’ , is a common tactic by fraudsters and other criminals in order to trick the recipient of the SMS to do something that benefits the fraudsters. It can take many guises, but one of the most impactful, and therefore dangerous, is when bank accounts are phished. In the last few months in Ireland , there have been multiple reports of SMS phishing attacks against account holders of one of the largest banks in Ireland – Bank of Ireland (BOI).

These recent attacks in Ireland share some of the same techniques that AdaptiveMobile Security have profiled in depth in other countries, but they also have specific ‘spoofing’ twists which may make them far more successful. We will examine them in detail here.

The Steps of the Attack

The attacks that has been occurring in Ireland works in two stages, with two different forms of spoofing. The following is from a real SMS text message that was received by a targeted number, and our analysis at the time:

Part 1: SMS Spoofing

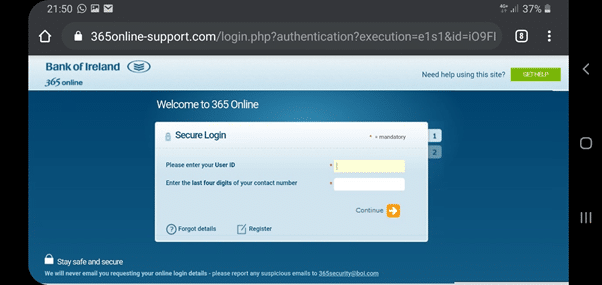

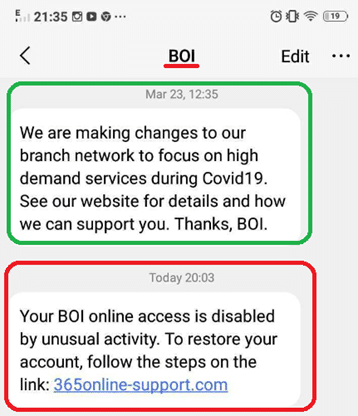

1) First of the all, the target receives a SMS text message purporting to be from BOI (Bank of Ireland). This screenshot contains a SMS text message telling the subscriber that they need to log on a banking website that looks similar to the ‘real’ BOI online banking website www.365online.com. Note the first covid19-related message at the top – this is actually a real communication from the bank, and we will come back to this later.

2) If the user goes to the website, they are presented with the following screen. The look and feel are quite similar to Bank of Ireland’s real online banking website, as the front-end code has been copied. Initially what they ask for here is User ID and the last 4 digits of the target’s phone number

3) If the target enters in these details, they are they asked for further pieces of information – in this case a date of birth and the first 3 numbers from their PIN. This is different from Bank of Ireland’s normal online banking login, which would normally ask for only one of the piece of information.

4) Regardless of whether the information entered is valid or not, the fraudsters need all 6 digits of the pin, not just the first 3, so in the following screen, they will ask for all of the digits, under the guise of the ‘wrong digits’ being entered the first time.

5) At this point, once all the details are added, the screen goes blank, however a different message could be displayed here if required.

Part 2: Voice Spoofing

Now the fraudsters have all the details, and so are able to access the targets account. However, to transfer any money to the fraudsters, they first need to be registered as a payee (a person to whom money can be transferred) on the target’s account. Most banks, including Bank Of Ireland, have some level of secondary authentication, in order to confirm the addition of a new payee to their account. In order to get money from the target, the fraudsters need this. While we did not observe these directly, based on media reports of successful attacks these are the next steps:

6) Using the target’s details (obtained from the malicious website), the attackers log on to the target’s bank account online, and request to add a new payee to the account.

7) A genuine SMS text message is automatically sent by Bank of Ireland to the registered phone number account holder, with a Security Code that is required to be inputted online on the account in order to add a payee.

8) The fraudsters then directly ring the target and they request the person to give the Security Code they received. According to reports, when the fraudsters make this call, they set the originating phone number making the call (the caller) to be the same number as a Bank of Ireland phone number.

Analysis of the Attack

As stated earlier, in general, this attack shares many characteristics to bank spam phishing attacks we have seen in other countries:

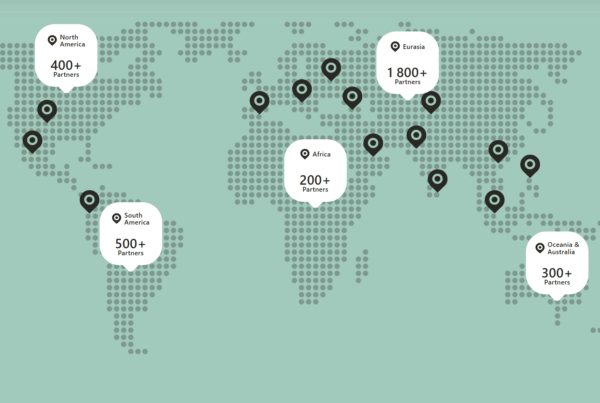

- The phishing sms was sent in the evening on a public holiday – in this case on Easter Monday (13th of April). Previously we have shown that bank phishing fraudsters often send their messages during unsocial hours (evenings, weekends and holidays). This visualization shows the predominance of attacks in the US that cluster around public holidays. Also as shown in our previous research fraudsters send more messages after business hours and around weekends. The reason this happens is if the target received a text during unsocial hours there is less chance they can contact security or fraud contacts within a bank. Even though we only have a single example here, it fits into the trend we have seen before – being sent at 8pm, and on a public holiday.

- There is wide-scale social engineering involved, the initial message puts a sense of urgency, and typically says the account is disabled or deactivated.

- It uses a registered url name: 365online-support[dot]com that resembles the site 365online.com they wish to imitate. The website itself at this address also copied almost verbatim the look and feel of the phished organisation. To further avoid detection, in this case the malicious url was only registered on the day of the attack (April 13th), which is quite standard for attacks of this type.

- Finally, there is no indication that the fraudsters know that those who receive the phishing SMS have a Bank of Ireland account or not. Here, like in the US, what is probably happening in this case is they simply target particular users (Irish mobile phone users), and with Bank of Ireland being the largest bank in Ireland, a certain percentage of those will have a Bank of Ireland account. This accounts for reports on twitter of people with no Bank of Ireland account receiving similar messages

Spoofing of the SMS sender

A big question though is why is the phishing SMS seeming to come to be coming from Bank of Ireland. What is happening here is the Sender address of the SMS: BOI, is being spoofed. ‘BOI’ sender is technically called an alphanumeric short code address, not a typical phone number address. It appears to be in the same thread as other, legitimate BOI communications, because when the handset receives messages from the same sender address, it places them in the same thread as a ‘convenience’. This is why real messages, like the preceding Covid-19 notification appear to come from the same sender as the phishing SMS (and any subsequent communications from the bank, using the BOI sender address would also get placed in this thread).

Green is a real message, and red is a phishing message

Clearly, the use of a sender address that seems to come from the bank, is a tactic that massively increases the potential ‘believability’ of the phishing SMS. We have previously covered in research on Banking SMS phishing in the US the value of the sending number, matching the ‘bank’ number. But in this case the spoofing of the actual shortcode used by the bank itself takes the subterfuge to a whole new level, and is arguably far more convincing.

From looking through old twitter reports of this, it seems that this tactic of spoofing the BOI shortcode has been used since at least November 2018 prior to this it was reported that other shortcodes, and source addresses have been used.

Another key point, is what is being ultimately obtained. In this case, the fraudsters don’t just want to get access to the victim’s bank account, they want to transfer money out of it. As a result, they need to do further social engineering to get the Security Code that gets sent to the victim. To do this they ring the victim, once the security code has been sent to them, and try to convince them to hand it over. Two things help them do this,

- One is that the victim receives a Security Code at all. The victim is probably feeling uneasy if they receive this message, as they may suspect that something is going wrong from their previous interaction with the spoofing site. A phone call purporting to be from the bank helps them feel that they are being taken care of.

- The fraudsters initiate the phone call to the victim, and here they spoof the phone number of the bank. This is the 2nd incident of spoofing in this scam, and this would also help convince victims to hand over the Security Code details, because again it seems to come from the bank.

The Trust Model

Technically speaking, the bank itself has not been hacked, nor has its systems been compromised. What it is potentially guilty of however, is its ‘trust model’. It is probable that the initial trust model of this system would have expected that the bank, and only the bank, could send messages from a BOI SMS address. Even though the bank only uses mobile phone networks for communications to bank account holders, it is reasonable to expect that bank account holders will initially assume that all communications from the same address (BOI) are genuine. Bank of Ireland do provide reminders they won’t ask for account details and examples of phishing attacks from the BOI shortcode, but at this stage if they are having to explain why some communications are valid and others not, then it is not obvious security, and a certain percentage of people will be defrauded. As long as BOI do any sort of communication on SMS, and phishing message seem to come from them too, then this confusion will arise. To put it another way, in standard SMS the sender is not authenticated, but the issue is the receiver has formed an impression that it is, and there is no way, on a standard SMS display on a handset that consumers can tell the difference, unlike email where you can look at headers and other features.

However, a bigger issue is the security of the mobile phone network. Simply put, for SMS, it should not be possible to send messages with an alphanumeric sender from sources that the mobile operator does not permit. Special software is needed to send spoofed SMS like this, this software ultimately connects to a messaging centre (SMSC). This means that mobile operators in Ireland, using SMS spam filtering logic, should be able to decide if they wish to block messages from sensitive Shortcodes like BOI, if they come from unexpected messaging centres. The same type of logic can also occur with phone calls – incoming calls that come from ‘sensitive’ phone numbers can be blocked, based on their source origin point and other characteristics, although due to the fact that it (the spoofed phone call) is the last stage in that attack, detecting and blocking the spoofed SMS should be the priority.

While this all sounds logic and desirable to implement, there are often conflicting interests. The Banks’ customers are being defrauded, but the Banks may not have a strong ability to force the mobile operators to put in place systems to make spoofing much harder. Similarly, the mobile operators are the ones who can help reduce the problem, but they often don’t even figure in the conversation as most people assume it is a bank issue only. In addition, it is possible that mobile operators may be reluctant to be seen to try to protect SMS given – in theory at least – it is an unsecured medium, even though in reality it is used to send critical communications.

At the same time, it is often not fair to single out individual banks or mobile phone operators. In this example we talk about Bank of Ireland, but other examples exist of other banks (in Ireland and in other places like the UK) being attacked in a similar way. Below is a screenshot taken from twitter of a UK bank – HSBC – being targeted in 2018.

In this case incidents like this provided the spur for changes in other countries. What is needed for is an industry wide effort – i.e. all banks and mobile operators in a jurisdiction to discuss what is needed to help security of messaging for banks – and other organisations that send sensitive communications, and for the operators to agree and put in place protections for them. These collaborative conversations have already happening in the UK and South Africa, and AdaptiveMobile are happy to be a part of them.

The end result is that countries can put in place industry-wide protection, and malicious messages that purport to be from Banks can be detected and blocked. For all enterprises – not just banks – even though SMS has a level of security, enterprises need to be aware that there are potential vulnerabilities to the SMS ecosystem that need to be taken into account when deciding whether to use it as a communication medium. By working with mobile operators, enterprises can determine how they have dealt with those vulnerabilities, such as implementing best practices in blocking SMS spoofing and other telecom industry recommended protections. Other specific changes by banks could also be considered, such as multi-factor authentication, in order to raise the security bar higher and make it harder to social engineer out sensitive information.

It is always upsetting when people are targeted, and far more upsetting and potentially life-changing if they are defrauded successfully. Ultimately the success or not of these attacks comes down to whether their social engineering is successful or not. Attacks like this will continue, but the fact they are able to successfully spoof source bank SMS addresses gives the fraudsters a massive advantage. While we can, and should request people to be wary of any text messages, emails or phone calls they receive, unless we want more innocent people in the community to be defrauded, then the overall industry within each country should come together and put in place methods and procedures to stop, or at least make more difficult, the tactics and techniques these criminals use.

This blog post originally appeared on the Adaptive Mobile Security Website and is re-used here with kind permission

Industries unite to tackle SMS fraudsters exploiting COVID-19 text alerts

The UK mobile, banking and finance industries along with the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) have joined forces to prevent fraudsters sending scam text messages that seek to exploit the Covid-19 crisis.