As phone networks quietly shift from legacy copper to internet-based connections, the FCC is moving to modernize how calls link between providers. Its new “Advancing IP Interconnection” proposal could redefine the legal and technical foundation of voice in the U.S. MEF CEO Dario Betti explains why this transition matters for the entire telecom ecosystem.

When you place a phone call today from a mobile, a desk phone your voice almost certainly travels over the internet, not old copper lines. That quiet revolution is what the USA regulator, the FCC, is finally trying to regulate directly.

In its “Advancing IP Interconnection” proposal, the agency signals that the rules built for the time-division multiplexing (TDM) era are nearing sunset and that IP-to-IP interconnection should be the new default for how networks link up to exchange calls. That move sounds technical, but it carries real-world stakes: who must connect to whom, on what terms, with what reliability, and under what legal authority. The telecom community should pay attention.

This critical review summarizes the FCC’s proposal, weighs the legal and market trade-offs, and puts numbers around how far the market has already moved to IP voice. The proceeding could force a long-deferred decision: whether interconnected VoIP is a Title II “telecommunications service” or an “information service.” That question determines how far the FCC can go in mandating interconnection and policing disputes. The FCC is a regulator of telecommunication service, but not the regulator of information services. In other words, the legal foundation comes first; the engineering and business arrangements follow.

What the FCC is proposing—and why now

A principled, narrow Title II move for interconnected VoIP, paired with targeted forbearance, would put the agency on solid ground to mandate fair IP interconnection while avoiding a regulatory overcorrection.”

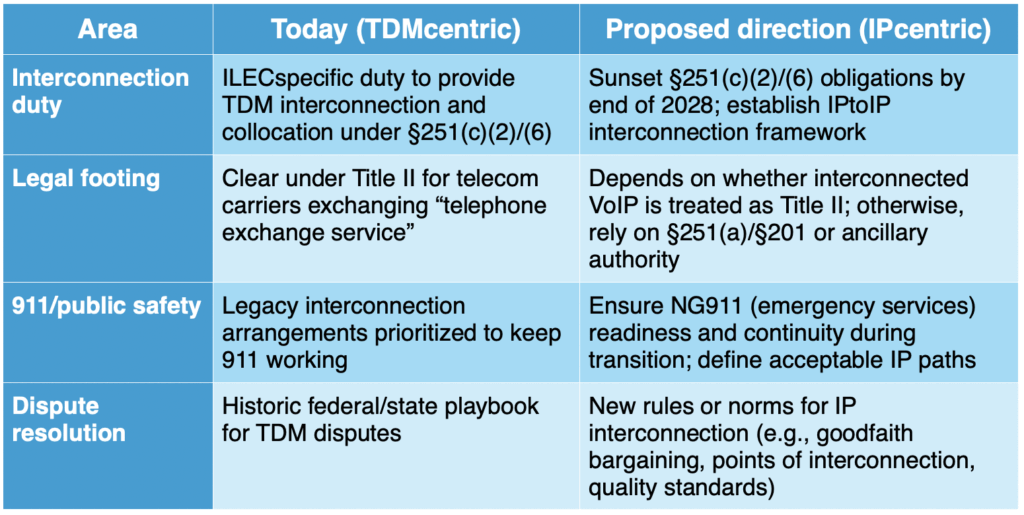

The FCC’s draft and subsequent fact sheet lay out a transition away from TDM obligations tied to Section 251(c)(2) of the 1996 Act, with a proposed sunset in 2028 and a new framework for IP interconnection. The Commission frames this as modernization: most voice traffic is already IP, yet there is no comprehensive federal framework for IP-to-IP interconnection. The agency asks how its authority under Sections 201 and 251(a) (which apply to “telecommunications carriers”) should apply in the IP context, and whether it must, at last, squarely classify interconnected VoIP to ground that authority.

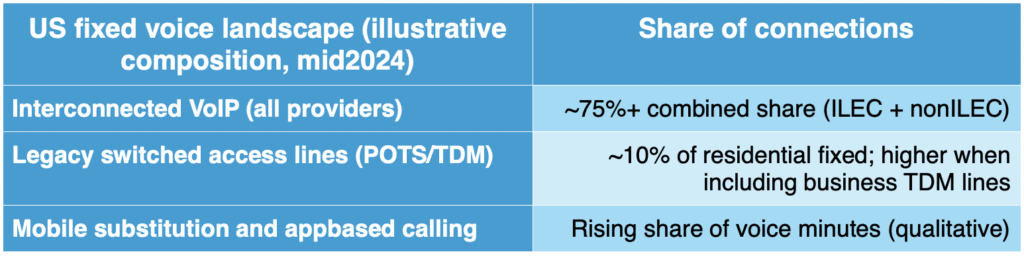

The timing reflects market reality. The FCC’s own Voice Telephone Services data show that fixed voice is now dominated by VoIP subscriptions, not legacy switched lines, and the latest “Advancing IP Interconnection” fact sheet states most voice traffic is IP-based, with traditional switched service a shrinking minority of residential fixed voice connections. By July 2024, 25.5% of the residential lines in the USA were considered ‘switched’ lines, and 74.5% were Voice over IP ones.

Why classification matters

The legal pivot is simple to describe and hard to resolve. If the FCC classifies interconnected VoIP as a Title II “telecommunications service,” it can impose common-carrier duties like just, reasonable, and non-discriminatory interconnection under Sections 201 and 251. If instead VoIP remains outside Title II, the Commission would have to rely on ancillary authority or voluntary “good-faith” norms, both weaker tools for forcing peering or resolving disputes.

The practical stakes: reliability, 911, rural, and dispute resolution

A move to IP interconnection promises cleaner handoffs, fewer transcoding points, and better call quality end-to-end. It also promises less duplication: carriers maintaining parallel TDM and IP interconnects is costly and brittle. But the risks are real. Public safety officials want assurance that interconnection transitions will not break 911 routing or degrade redundancy. Rural carriers, transit providers, and small VoIP operators want clarity on points of interconnection, settlement practices, and whether incumbents can refuse direct IP interconnects in favour of the public internet. The draft asks for exactly this evidence and comment, including the impact on NextGeneration 911 and the contours of any “good faith” negotiation duty.

Below is a concise map of the rule shift the FCC is floating.

Quantifying the IP voice reality

To assess urgency, look at the numbers. The FCC’s official Voice Telephone Services report shows the composition of fixed voice subscriptions has flipped decisively toward VoIP. As of mid2024, traditional switched lines are a small and shrinking minority of residential fixed connections, while interconnected VoIP dominates. The “Advancing IP Interconnection” fact sheet also states that most voice traffic is now IPbased. Put simply: policy is catching up to market practice.

Sources: FCC Voice Telephone Services, status as of June 30, 2024; FCC fact sheet (Oct. 2025).

The case for action

On the merits, the FCC is right to modernize. Keeping mandatory TDM interconnects distorts investment, forces parallel legacy infrastructure, and prolongs awkward IPtoTDMtoIP bridges that add cost and degrade quality. For consumers, coherent IP interconnection can mean fewer failed call handoffs, more consistent HD voice, and faster troubleshooting across providers.

A clear federal framework could also reduce the volume and ferocity of private peering disputes. Today, there is no common set of expectations for direct IP interconnection among voice networks. That vacuum invites brinkmanship (rerouting through the public internet, quality cliffs, or refusal to upgrade) that ultimately harms end users.

Finally, public safety demands predictability. The transition to NG911 is uneven; locking in minimum standards for IP interconnection, redundancy, and quality during and after the sunset is essential.

The caution flags

Two caution flags stand out. First, classification. If the Commission attempts to impose robust IPtoIP duties while leaving interconnected VoIP unclassified or outside Title II, courts may view the rules as resting on shaky ancillary ground. The agency would then risk having a central piece of the transition struck down. Conversely, a full Title II classification of interconnected VoIP would bring clarity but could also pull additional obligations (USF, disability access, potential tariff consequences) onto providers—some of which may require a careful approach to avoid overreach.

Second, implementation. Sunsetting TDM by the end of 2028 is aggressive for small rural carriers and PSAPs (911 centres / the emergency call centres) still mid-transition. The record will need concrete migration plans, measurable quality benchmarks, and a crisp definition of acceptable “interconnection over the public internet” (if any) to prevent degradation. The Commission’s questions on points of interconnection and good faith bargaining are necessary but must culminate in rules that are enforceable without recreating TDM-era micromanagement.

A pragmatic path forward

The cleanest, litigation-resistant path is to decide VoIP’s status and then tailor the rule. If the FCC classifies interconnected VoIP under Title II but also drops nonessential obligations, it could:

- Impose a narrow, technology-neutral duty to interconnect IP-to-IP on just and reasonable terms;

- Require good faith negotiation and define points of interconnection with flexibility for network topology and cost causation;

- Set quality and reliability minimum (especially for 911) that prevent “public internet dumping” where it harms call quality; and

- Establish a light-touch dispute process that resolves interconnection stalemates quickly.

If the agency instead avoids reclassification, it should be candid about limits and prioritize transparency obligations, standardized technical profiles for IP interconnects, and a backstop adjudication process. That would still beat today’s patchwork, though it would likely leave some disputes unresolved without stronger authority.

Bottom line

The FCC’s “Advancing IP Interconnection” initiative is overdue and directionally right. The market has already moved—most voice traffic is IP-based, and legacy TDM requirements are increasingly a drag, not a safety net. The hinge is legal clarity. A principled, narrow Title II move for interconnected VoIP, paired with targeted forbearance, would put the agency on solid ground to mandate fair IP interconnection while avoiding a regulatory overcorrection. Consumers would see fewer dropped calls and better quality; providers would see fewer standoffs and cleaner incentives to invest.

What the agency should not do is leave the foundation ambiguous. In interconnection, ambiguity invites disputes, and disputes degrade service. The point of this proceeding is to replace ambiguity with an IP-era rule of the road.