Michael Becker speaks with Justin Bryant, a Stanford J.D. and Schwarzman Scholar to discuss how the world views and takes action on personal data regulations. They review the landscape of global data regulations and the “The Internet & Data Triad,” i.e., the three philosophies driving personal data regulation. They also review the transplant effect and how some regions, like Africa, are struggling with the western view of personal data protection.

In my pursuit to understand the personal data and identity marketplace, I sat down with Justin Bryant, a Stanford J.D. and Schwarzman Scholar, to discuss the current state of the world’s personal data regulations.

Justin keenly raises two important macro considerations to illustrate what’s happening with personal data regulations in Africa and around the world.

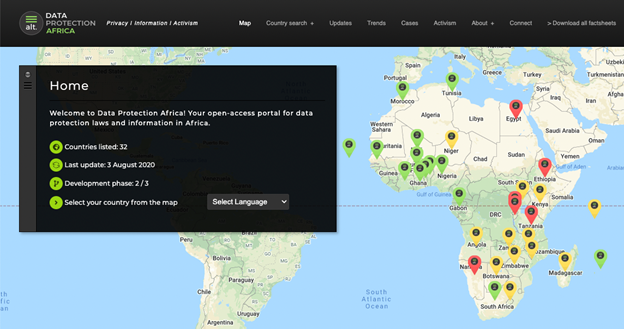

The first of these two considerations is what I call the “The Internet & Data Triad” and the second is The Transplant Effect, a legal concept referring to what happens when a country imports regulations. Justin also shares his 2020 work on “Data Protection Africa,” an Alt Advisory initiative that reports on the state of personal data regulations in 32 of the 54 countries on the African continent. Our conversation concludes with Justin sharing his view on what actions people, governments, and enterprises should consider taking to thrive in today’s, and prepare for tomorrow’s, regulatory environment.

There are literally hundreds of data protection laws and regulations being drafted, reviewed, and introduced worldwide. Understanding these laws is important, as they affect how business is conducted and with enterprises and citizens in their respective countries.“

Data Protection Regulations

The role of government is to provide national defense, administer justice (i.e., oversee law and order), and provision public works. In this capacity, if you’ve not noticed, governments worldwide have been busy instituting data protection legislation that encompasses all three of these roles. The legislation that often tops most of the lists includes:

- Global Data Protection Regulation (GRPR), the omnibus EU regulation that came into force in May 2018.

- California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), the California regulation that came into force in June 2019, and there is its extension—the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA)—that will come into effect in January 2023.

- Brazilian General Data Protection Law (LGPD), which was introduced in September 2020.

- Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), China’s regulation came into force in August 2021.

There are literally hundreds of data protection laws and regulations being drafted, reviewed, and introduced worldwide. Understanding these laws is important, as they affect how business is conducted and with enterprises and citizens in their respective countries.

Data protection regulations have a significant impact on every aspect of society worldwide. They are nuanced. They are heavily influenced by each nation’s commercial, social, cultural, historical, and political circumstances.

Data Protection Africa

During our conversation, Justin referenced a project he worked on with Alt Advisory in 2020. Justin and the team at Alt Advisory developed the Data Protection Africa Portal. This portal is an open-access portal for data protection laws, information, and activism in 32 African countries. It provides a review of the law in each country, including its:

- Status (non-existent, proposed, under review, postponed, enforced)

- Data definitions

- Data collection and processing rules

- Registration requirement

- Enforcement methods and files

- Cross-border transfer rules

- Security and data breach notice protocols

Other Personal Data Regulation Maps

Personal data and privacy regulation is a moving target. There are a myriad of institutions worldwide keeping track of the ever-changing global, national, regional, and state regulatory landscape. Here are two more samples to add to the one above:

- DLA Piper, a global law firm, maintains a useful portal, “Data Protection Laws of the World.” They place each country in one of five regulation and enforcement categories (heavy, robust, limited, moderate, none).

- The International Association of Privacy Professionals maintains a “Global Comprehensive Privacy Law Mapping Chart (Updated: Nov. 2021)” and a “US State Comparison Table (Updated: Sept. 2021)” that I’ve found to be helpful resources for keeping track of and understanding the current and future trajectory of regulations.

Internet & Data Triad

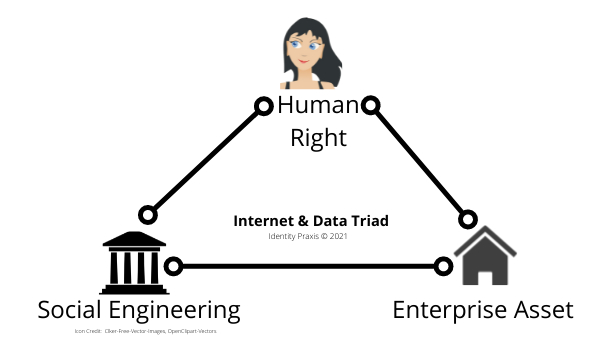

In our conversation, Justin and I explain the three primary internet and data philosophies that are in play around the world, what I’m calling the “Internet & Data Triad.” They are:

- Data is a human right: Followers of the “data is a human right” philosophy believe that the ability to own and control data that is produced by and about an individual is a central human value simply because we exist as human beings. The idea of data as a human right is grounded in the United Nations 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which comprises 30 articles, including the right to life, to own things, and to privacy. In 2011 the United Nations introduced another right, the right to Internet access. The “data as a human right” philosophy is predominantly followed throughout Europe but has recently been adopted in California, India, and other states and countries throughout the world. Today, this philosophy is primarily supported through people-centric legislation, however, the emergency of the self-sovereignty approach–a technology grounded method to give people control of their data–looks promising for making this approach possible, at scale.

- Data is an enterprise asset: Followers of the “data is an enterprise asset” philosophy believe that the enterprise that mines and refines the data owns the data. The data as an economic asset model is predominantly followed in the United States and similar countries. This philosophy gives rise to the surveillance economy.

- Data is a social-engineering tool: Followers of the “data is a social engineering tool” philosophy believe that data is a tool to be used to manage and engineer the social structure. This philosophy is predominantly followed in China and related countries. The ruling authority looks to have complete control over the Internet and data. This philosophy has well-documented abuses of power and is said to threaten civil liberties.

Other Considerations

In addition to the three philosophies, to grasp a nation’s law fully, government leaders, enterprise executives, and individuals should consider the general legal approaches used in a country and the country’s social orientation. For instance, in Europe the laws tend to follow an Omnibus approach, meaning that the law universally applies regardless of the market sector. In contrast, the United States follows a sectoral model, meaning the laws are applied differently across market sectors (e.g., tech, healthcare, finance, education). As an aside, Daniel Solve, a leading legal-privacy pundit, argues that the sectoral approach has its problems.

In addition, a country’s cultural orientation should be considered. For instance, in Europe, the laws tend to inform what can be done, while in the United States, they inform what should not or can’t be done. Moreover, when considering personal data laws, a country’s cultural approach to privacy should be considered, i.e., collectivism vs. individualism. Collectivist culture tends to stress the importance of the community, while individualism culture focuses on each person’s rights and concerns. These factors influence the ability of a country’s personal data position to be drafted, understood, adopted, and enforced.

A world of “AND”s Not “OR”s

So that there is no uncertainty of doubt, while various regions of the world lean toward one internet and data philosophy over the others, all three philosophies are present and working in every region and country. For example, while the U.S.’s primary internet & data orientation is data as an enterprise asset, the two other philosophies are also present. States like California, Colorado, and Virginia have already enforced human rights legislation, and other states are soon to follow. And yet, the data as a social-engineer tool thrives through the practice of the credit score, for example.

The Transplant Effect

Data protection regulations have a significant impact on every aspect of society worldwide. They are nuanced. They are heavily influenced by each nation’s commercial, social, cultural, historical, and political circumstances. In addition to The Internet & Data Triad and the general data protection cataloging efforts underway around the world, Justin raised another concept that I found to be a useful lens to look through when considering the impact of regulation around the world: “The Transplant Effect.”

The Transplant Effect suggests that imported laws and regulations will be less effective than home-grown laws and regulations that evolve naturally and appropriately learn and borrow from other regulations. Putting this into the context of data protection regulation, Justin points out that many African countries “largely copied and pasted sections of the GDPR laws from Europe.” They did this, Justin asserts, to align economically with Europe. However, GDPR is the byproduct of decades of internal EU legislator conversation and regulatory development, with strong ties to the 1995 Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC. Moreover, Europe tends to align with individualism, thus the focus is on individual human rights. African countries don’t have the luxury of this history.

Justin notes, “For laws to really take root in society, they have to have buy-in from the citizens.” African countries that simply “adopted” GDPR regulations may impact the transplant effect. The theory suggests that these African countries will struggle to roll out GDPR without it being tailored to local customs and regulations. This is because the local markets don’t benefit from decades of collaborative discussion, and they are culturally oriented to collectivism. They will need time. Moreover, unlike Europe, which puts the individual ahead of the group, African cultures tend to put the group’s priorities first. Therefore, many of the GDPR premises are culturally foreign.

It will be important for governments and enterprises to consider the implication of the transplant effect when working with African countries. They need to be sensitive to the circumstance; they may be surprised when they encounter misunderstandings and find the African flavor of GDPR different from their own. Moreover, the next boom of Internet adoption will come from regions like Africa, as evidenced by the GEOFred illustration below. The world will need to figure out what to do with all this data.

What Do We All Need to Do?

Justin concludes our discussion with some sage advice.

He notes that more and more people from the developing world will be coming online in the years to come. They will be younger. He advises governments to expect tensions as these digital natives will have expectations, like economic inclusion and new digital native service (e.g., finance, security, governance), that the traditionally slower regulatory process will have trouble meeting. He advised them to engage “sharp people” who have an “ear to the ground” and understand the circumstances so that they can help bridge the divide.

For enterprises, he suggests that they prepare, as “breaches are going to become increasingly harmful in ways that we’ve not seen before.” While he said individuals are ultimately accountable for themselves, he suggests that leading enterprises who develop a competitive advantage in customer service and education could thrive.

Finally, Justin encourages individuals to be vigilant. They need to educate themselves and understand the data that their online and offline activity generates. They need to pay attention to regulatory developments and advocate for themselves to be sure their voices are heard.

As of 2020, 10% of the world’s population will be covered by one form of human rights legislation or another; according to Gartner, this number will grow to 65%. There is one thing for sure we can expect in the months and years to come: change.